Community development, Urban

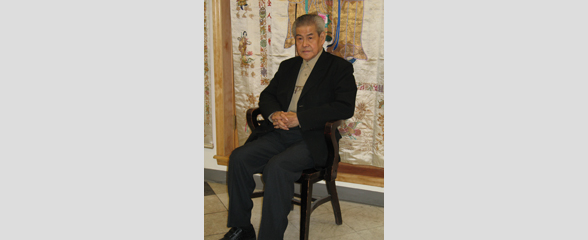

2008.040.019 Oral History Interview with Ho Ying Pang March 16, 2008

Pang Ho Ying was born in Taishan, China, but grew up and spent a large portion of his life in Hong Kong until he moved to New York with his wife in 1988. Interestingly, his family was divided on both the East and West coasts: he and his two brothers settled in New York, while his two sisters moved to San Francisco. Pang vaguely remembers his first impression of New York upon his arrival as relatively less modern than Hong Kong, claiming that Chinatown appeared backwards since it lacked the modern buildings and technology of Hong Kong. Regardless, Pang perceived Chinatown as a friendly and supportive environment that deeply valued family relationships and friendships.

Though Pang did not plan or arrange employment in the United States before immigrating, he trusted he would find a suitable job. After two months, he found work through his younger brother as a general handyman or “gofer†at the Music Palace theater. Pang eventually became the director of the theater and managed the daily operations until he retired. In his interview, Pang walks through the history of the Music Palace and offers his opinions on what ultimately brought about the movie theater’s demise in 2000. Pang asserts that the reason the theater went out of business was because it was no longer in demand after the popularization of the relatively cheaper videotape rental. As the theater began running deficits and attendance records started dwindling, Pang recommended to the Hong Kong based theater owners that the business close its doors, bringing an end to the last movie theater that specialized in Hong Kong cinema in the United States. Pang recognizes the pragmatic reasons for closing the Music Palace but still expresses regret that the theater could no longer serve as a community gathering place for residents and visitors alike.

Pang goes on to identify some of the changes that he has witnessed in Chinatown more broadly, particularly that many old buildings had been upgraded and renovated, empty and vacant lots had gradually been built up, rent prices had skyrocketed, and the general aesthetics of the neighborhood had improved. He also hints at a generational shift and ethnic tension, comparing the new wave of Fukienese immigrants with the older generation of mainland Chinese immigrants to the neighborhood. While Pang notes that his children do not desire to return to Chinatown, he still explains that he hopes to remain living in Chinatown because of its convenient location, the Chinese food and tea, and general familiarity.

2008.040.022 Oral History Interview with Spring Wang September 8, 2008

Spring Wang is an independent developer who was born in China and raised in Taiwan. In this oral history, she discusses her experience of moving to the United States in 1968, where she attended college and became a Marxist heavily involved in political and social movements. One organization with which she associates herself is Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), a group devoted to talking about social services, equal employment opportunities, and housing development. She reflects on her experience in New York’s Chinatown, paying particular attention to the infrastructure and ongoing development that trickles into Soho, the Lower East Side, and Tribeca.

Events like September 11th and the global economic crisis come into play when Wang analyzes the demographic shifts in the community. According to Wang, new Chinese immigrants are more self-confident and forward-looking in contrast to earlier immigrants. She believes that because Chinatown is a small area, the institutions or physical aspect of the neighborhood is more essential than the residential population to the survival of Chinatown. She proposes that Chinatown builds larger institutions, advocating for the creation of places with more cultural spirit and symbolic significance to act as a “magnet†for the people.

2008.040.027 Oral History Interview with Sing Kong Wong February 8, 2008

After being petitioned by his wifes family, Sing Kong Wong, a former administrator for a government agency in China, immigrated to New York in 1980 where he worked as a presser in a garment factory. Wong illustrates the poor working conditions in the garment factories, commenting on the lack of sanitation, violations of workers rights, and inadequate benefits and welfare. He explains how the steady decline in the garment industry has been especially problematic for immigrant populations, as they are unable to find other jobs and have limited financial means to pay the rising rent. Wong believes that the decline in garment factories began with the U.S. legislation that permitted jobs to be outsourced to Mexico, China, and India. After the events of September 11th, the situation worsened as landlords demanded higher rent and as zoning changed residential areas to commercial and business spaces.

Wong mentions that as a way to remember his past life and to share important life lessons with future generations, he has photographed personal and historically significant subjects and occurrences relevant to his life and experiences. Such subjects include the harsh conditions in garment factories, life in Chinatown, and the events of September 11th. He continues to describe the changes in Chinatown occurring over the past thirty years, like the improving tolerance and relationships between ethnic and provincial groups and the greater appreciation for Chinese culture and traditions.

Finally, Wong elaborates on his views regarding gentrification, worrying that people with lower-incomes will suffer the consequences of uncontrolled rent prices, eviction, real estate development, and a poor job market. He suggests that the government should be more involved in maintaining the parks, providing more recreational programs for the community, and fixing local traffic problems. Wong asserts that progressive and proportionate improvements are necessary, but these improvements must serve all residents and not just the wealthy.