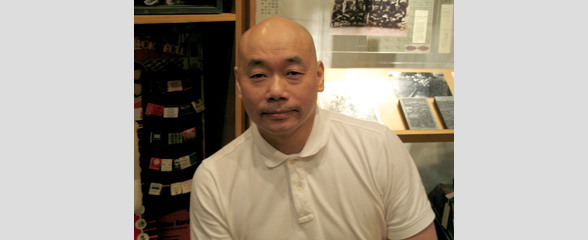

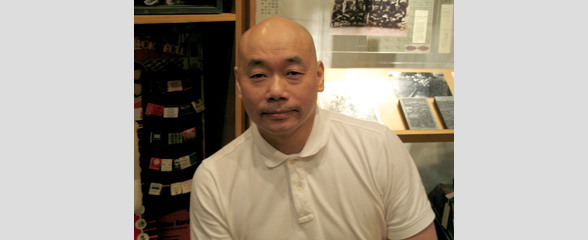

| Howard Pyle talks to MOCA about his experiences moving into the broader Chinatown area during the booming dot-com years of the 1990s and how he has witnessed things change since then. He offers listeners some interesting context for the rise and fall of the dot-com bubble and how 9/11 affected many parts of lower Manhattan and led to shifts in population. Howard also goes into detail about the punk scene in DC where he was from and how he felt when he first moved to NYC and was forced to learn the cultural geography. He shares his experience with the Yellow Arrow Project as well as his thoughts on what connects people to the spaces they visit or inhabit. The conversation concludes with Howards thoughts on the term gentrification and the real-world impacts of gentrification on NYC and the artists who live there. |  | Kayo Ong, a long-time Chinatown resident and landlord, speaks extensively about the violence with which Chinese residents and he were confronted after relocating to Chinatown in the 1960s. At that time, Ong describes the Chinatown community as highly racist and discriminatory, mentioning the strained relationship between Chinese and Italian residents in particular and the popular slang terminology that sprang up as a result of racial stereotyping and labeling. Ong explains that his initial interest in the martial arts was to learn how to protect himself, and later, was a source of physical, spiritual, and mental development.

Ong specifically recalls hearing the beating drums that accompanied the traditional Chinese lion dance and his associated realization that Chinese people had finally accomplished public recognition and acceptance into the community that is now called Chinatown. He remembers that during his childhood and adolescence, he attended Kung-Fu double-feature films at the local theaters including the Music Palace and Sunsing Theater, both of which he believes may have closed due to technological modernization, as well as the occasional outbreaks of violence during the movies instigated by rival gangs. He closes his interview by commenting on how he is coming to terms with some of the neighborhood changes, such as the loss of “real†Chinese food, saying it has been replaced by restaurants that cater to an American sense of Chinese cuisine. |  | Larry Goodman, todays owner of his familys corporation Grand Machinery Exchange, Inc., recounts how his first generation Polish grandfather founded the company in 1927. Goodmans father Jerry and uncle Isidore took control of the business in 1947, and Larry Goodman later succeeded his father in 1983. According to Goodman, Centre Street machinery dealers were predominantly Jewish and were often afraid of non-Jewish “outsiders.†These business men were concerned with gaining respect and carried physical and psychological hardships because of this work ethic. Goodman also recalls the mixture of unity and intense competition between Jewish and Italian machinery dealers, the whole of which was referred to as the “forty thieves,†since most of the dealers were considered unrefined and were occasionally accused of having questionable business ethics.

Goodman reminisces about Chinatown as the industrial center of Manhattan, where he saw gradual sociological changes between the 1950s and 2000, including industry, hardware, and supporting retail spaces systematically leaving the area. Goodman sold the Grand Machinery Exchange shop building in 2005, explaining that business was no longer viable on Centre Street. He also notes the growing presence of Chinese-owned businesses on Centre Street, incorporating the neighborhood as a part of Chinatown rather than SoHo. Goodman reflects on how Centre Street has cycled through machinery and manufacturing, the garment industry, living-working spaces for creatives, and now finally to expensive developments. Furthermore, when asked to imagine the future of Chinatown, Goodman argues that money will dictate the outcome as part of a natural economic cycle. In his eyes, wealthy populations will move into the area, demand more luxury services and support and retail to accommodate their lifestyle and living spaces, and replace “mom and pop†establishments that can no longer afford to remain there.

|  | MOCA sits down with Jan Lee to discuss his familys longstanding presence in Chinatown and some of the changes that he has witnessed over the decades as the owner of 21 Mott Street. Jan shares the story of how his family first became rooted in Chinatown when his grandfather arrived there at the end of the 19th century. He explains the changes that occurred in Chinatown during the huge wave of Chinese immigration in the 1970s, especially regarding the rise of violence and gangs in the area. Jan also shares the story of how his sister fought this trend through the Chinatown Community Young Lions program and shares anecdotes about his participation in the program. The conversation also delves into Jan’s thoughts on gentrification, both current and past. He offers his thoughts on the importance of Chinatown’s community stakeholders, the internal divisions in Chinatown, some of the dangers posed by external investment, the role that NYC is currently playing, and the role that he believes the city should play to encourage responsible development. |  | Kam Mak is an artist who emigrated with his parents from Hong Kong to the United States at age ten in 1971. In this interview, he vividly describes growing up in an old tenement building on Eldridge Street and becoming involved with street kids during the seventies. He mentions the strong presence of street gangs during his childhood as well as the turning point during his youth that redirected him towards art as an escape from getting into trouble. Mak also discusses conceptual ideas that inspire his artwork, which is heavily influenced by his sensory impressions of the Chinatown neighborhood and culture. He notes the changes in neighborhood dynamic since then, observing differences in population, safety, and lifestyle. After moving out of Chinatown in the early 90s, Maks art became a means to reconnect or save his ties to the Chinatown community. He goes on to describe his work writing and illustrating his childrens book My Chinatown and designing a series of Lunar New Year stamps for the U.S. Postal Service. Reflecting on how Chinatown’s identity is rooted in its low-income and immigrant residents, he laments about how the forces of gentrification could eventually erode Chinatown to a “fake†shell of its former glory. |  | In her interview, Mannar Wong describes the changes she has seen in Chinatown spanning the past forty years. Emigrating with her mother and father from Hong Kong in the early seventies, Wong was raised in Chinatown and moved to Brooklyn with her parents in the eighties when she was a pre-adolescent. In the nineties, she later returned to the neighborhood she now refers to as “Chinatown Little Italy.†Wongs parents initially disapproved of her decision to move back into Chinatown, a place they regarded as a “starting point†for immigrants.

However, Wong considers present-day Chinatown “hip and appealingâ€, which she says was the partly the result of a community of creative types who renovated the area and acted as trailblazers for others to settle there. Wong classifies gentrification as, for the most part, making a place more desirable to people. Although, she warns that the question of whether gentrification is positive or negative is a loaded question – for instance, while she enjoys the appeal and “creature comforts†of the neighborhood, Wong predicts that she will eventually move out due to rising rent prices. Moreover, even though she does not consider herself an activist, she disagrees with small family-owned businesses being replaced by businesses that are not useful to the community.

|  | Margaret Chin, Deputy Executive Director of Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), shares her experiences immigrating to the United States with her family in 1963 and growing up on Mulberry Street, and later Mott Street, both of which were inhabited by predominantly Chinese and Italian populations. Her memories of Chinatown reveal that it was a much smaller community then, which eventually expanded and became more vocal about Asian American rights.

As a young adult, Chin became increasingly interested in and involved with volunteering for AAFE, an advocacy organization established in 1974. AAFE played a key role in organizing Chinatown tenants to fight against eviction, harassment, and gentrification in the housing developments; to secure decent housing for low-income families; and to expose the threat of development and tourism on Chinatowns “authenticityâ€. Chin believes that the organization has succeeded in staying true to its mission by actively organizing and changing policy and legislation for the benefit of the community.

|  | Mr. and Mrs. Chan, founders and owners of the long established and renowned coffee

shop and restaurant, Mei Lai Wah, in New Yorks Chinatown, are both Taishan natives, who claim that New York, especially their restaurant, is home to them. Upon arrival, Mr. Chan was employed at a bakery, the culinary training from which he later applied to his own business, Mei Lai Wah. Mr. Chan explains that he runs his business like a family and has not changed anything since he first opened it in 1968. He celebrates that his employees, who are also from the same village as Mr. Chan, have stayed with the business since its opening. As a result of rising rent, Mr. and Mrs. Chan have witnessed family-owned business closures and fear that the increasing expense of living in Chinatown may drive Chinese immigrants to settle outside of the unique cultural community. Despite their concerns over rent increases and their employees increasing age, both Mr. and Mrs. Chan hope to sustain their beloved business for as long as possible. Ultimately, when Mr. and Mrs. Chan decide to retire, they will not be handing down the restaurant to their children since none of them have expressed interest in continuing the operations of the business or living in Chinatown.

|  | Pang Ho Ying was born in Taishan, China, but grew up and spent a large portion of his life in Hong Kong until he moved to New York with his wife in 1988. Interestingly, his family was divided on both the East and West coasts: he and his two brothers settled in New York, while his two sisters moved to San Francisco. Pang vaguely remembers his first impression of New York upon his arrival as relatively less modern than Hong Kong, claiming that Chinatown appeared backwards since it lacked the modern buildings and technology of Hong Kong. Regardless, Pang perceived Chinatown as a friendly and supportive environment that deeply valued family relationships and friendships.

Though Pang did not plan or arrange employment in the United States before immigrating, he trusted he would find a suitable job. After two months, he found work through his younger brother as a general handyman or “gofer†at the Music Palace theater. Pang eventually became the director of the theater and managed the daily operations until he retired. In his interview, Pang walks through the history of the Music Palace and offers his opinions on what ultimately brought about the movie theater’s demise in 2000. Pang asserts that the reason the theater went out of business was because it was no longer in demand after the popularization of the relatively cheaper videotape rental. As the theater began running deficits and attendance records started dwindling, Pang recommended to the Hong Kong based theater owners that the business close its doors, bringing an end to the last movie theater that specialized in Hong Kong cinema in the United States. Pang recognizes the pragmatic reasons for closing the Music Palace but still expresses regret that the theater could no longer serve as a community gathering place for residents and visitors alike.

Pang goes on to identify some of the changes that he has witnessed in Chinatown more broadly, particularly that many old buildings had been upgraded and renovated, empty and vacant lots had gradually been built up, rent prices had skyrocketed, and the general aesthetics of the neighborhood had improved. He also hints at a generational shift and ethnic tension, comparing the new wave of Fukienese immigrants with the older generation of mainland Chinese immigrants to the neighborhood. While Pang notes that his children do not desire to return to Chinatown, he still explains that he hopes to remain living in Chinatown because of its convenient location, the Chinese food and tea, and general familiarity.

|  | Paul Kazee, one of the founders and former director of the organization Subway Cinema, played a significant role in showcasing Asian films to the New York public after the closing of Music Palace, a theater that specialized in showing Hong Kong films. Starting in 2000, Subway Cinema spent its first two years organizing events centered on dispelling what the group perceived as a misconception that Hong Kong cinema was degenerating and uninteresting. After gaining strategic connections and networking with NYU students, Subway Cinema achieved higher attendance which allowed them to began expanding to other Asian cultural films. The highlight of the organization’s work is its annual New York Asian Film Festival. The Festival generally lasts for two weeks and attracts large crowds of both Asian and non-Asian audiences, mostly comprised of students.

In terms of changes that have occurred in Chinatown, Kazee explains that he, along with numerous others, feel it is unnecessary to visit Chinatown now since much of the shopping available in Chinatown is now available elsewhere, particularly online. Kazee also reminisces about the pagoda-inspired phone booths, morning Tai-chi exercises in the local parks, and small local Asian video stores, all of which have gone by the wayside. Finally, he also briefly reflects on his feels towards gentrification, describing how he eventually realized how he himself contributed to the process of change in New York’s neighborhoods.

|